1923 (Approximate) - April 14, 2010

On January 1, 1945, Flight Lieutenant Ed McKay crashed upon approaching Eindhoven, after the air base had been shot-up. See story about Operation Bodenplatte for more detail.

He wrote the following for the July 1995 Typhoon Pilots' Newsletter: "After writing off F3Z Typhoon in a crash landing at Eindhoven, January 20, 1945 due to flak damage and engine failure, I was posted on leave, with a couple of other pilots. We are told it would be a skiing holiday in the French Alps. We went by Dak to Paris and spent two days in a huge Paris mansion, the wartime quarters of senior German officers and property of the Rothchilds. Food was excellent and a luxurious bar-lounge was busy all day with a collection of uniforms from just about every branch of the Allied services. In the middle of one celebration, drinking French 75s (Champagne and cognac) we were joined by a group from the next table which included David Niven. He was wearing black shoulder pips, which we understood involved some army intelligence outfit engaged in behind-the-lines action. It was a great party, and Niven was just one of the gang but did some entertaining. A brief tour of Paris and the next day we were on our way to Lyons by train. There was a brief stay in what must have been the premier hotel in the city square and we were joined by various types from Allied Forces, grouping for our final trip into the French Alps. I remember two incidents: watching what seemed an endless line of German POWs from the Battle of the Bulge, guarded by US troops with machine guns. I remember noting what a ragged, demoralized gang, Hitler's supermen had become. I remember a bridge game in the lobby with a French civilian couple. our mutual broken English and French were enough to have a good game. There was a long ride in the back of an army truck through the mountains to Mejeve, a village in Chamonix, Haute Savoie, which is a famous site of Olympic skiing events. Our small hotel was the Soleil D'or. This and many others were occupied by officers, mostly airforce from many countries and units. After briefing, we were fitted with equipment and given hours of instruction on the lower slopes before challenging the big runs from the top of Mounters Rochebrunewhich we reached by teleferique or cable car. This was quite an experience, dangling and swaying on a wire that seemed to be a thousand feet in the air. We quickly adapted to skiing at a terrific clip down the mountain for what seemed about a two mile trip. Refreshments at the bottom in a chalet bar. Our food at the Inn was quite a relief from British Army Rations at Eindhoven. There was a lot of gambling until the small hours with thousands changing hands in every official and occupied territory currencies. Exchange rates were quickly determined. As I remember, everything was paid for by some wealthy Belgians via the Red Cross. It was a great experience, with only one broken leg in the group."

McKay was a member of 193 RAF, 412 RCAF and 438 RCAF Typhoon Squadrons. On pages 27, 164-166, 176, and 186 in Typhoon and Tempest by Hugh Halliday, more information about Ed McKay can be found.

Submitted for the Typhoon Pilots' Newsletter, October 1997, McKay wrote the story NOT IN THE LOG BOOK. "We all had experiences not recorded in our log books that were humorous, adventurous, interesting and exciting, particularly overseas. I learned to ski in the French Alps, and was stranded on a mountain top after breaking a ski, and the the cable car went with u/s. A month before D-Day, stationed at RAF/RN Station Gosport at Portsmouth, I instructed ground crew for two days in the use of the Sten gun. For many nights, our area was covered in a smoke screen. The fields and villages around us were filled with the massive buildup of supplies and troops for the invasion. There was a fear of a German paratroop drop. We pilots were given a crash course in Sten firing, did a creditable job of not shooting each other or getting thumbs crushed in the breech. We processed lineups of cooks, clerks, irks, etc. then issued them with a Sten each plus clips. When it was all over, we wondered who in hell would get shot first by a Sten: an airman or a German. In the process we pilots became reasonably good shots. Another duty at the time was censoring mail that was forwarded to Gosport from the Isle of Wight before being posted. Up to that point, I thought I new a lot about life, but reading hundreds of letters was an education. Along with Pete Thorne, a fellow pilot from 193 RAF Typhoon Squadron, stationed at Harrowbeer South Destroyer on action station in the Channel. In early 1943, RAF and RN London brass were in a row about the RN shooting down our planes, mostly fighters. RAF blamed RN for poor a/c recognition. RN blamed RAF for buzzing ships on full alert without proper warning. Decision was made to place 2 fighter pilots on board every fighting ship for about 10 days and report back. It was a fascinating experience and we both acquired immense admiration for the Navy. The destroyer is the equivalent of a fighter plane in the Navy: fast and highly maneuverable. We zipped in and out of convoys off the Channel coast, had a go at sinking drifting mines with a .303 (finally sunk by Pom Pom guns); went fishing RN style by dropping depth charges, after which a small boat lowered and seaman scooped up the flopping stunned fish. We had some great fish dinners. Finally, we chased after some German E-Boats, firing 4" guns at nights, star shells and all, before returning to Plymouth. Our report was brief and what we already knew. Any idiot who buzzed an RN ship on station deserved to be shot down. Our destroyer crew whom we greatly admired were highly trained, instant reacting pros, highly nervous about approaching a/c; their a/c recognition was almost zero and the hull of a destroyer is extremely thin."

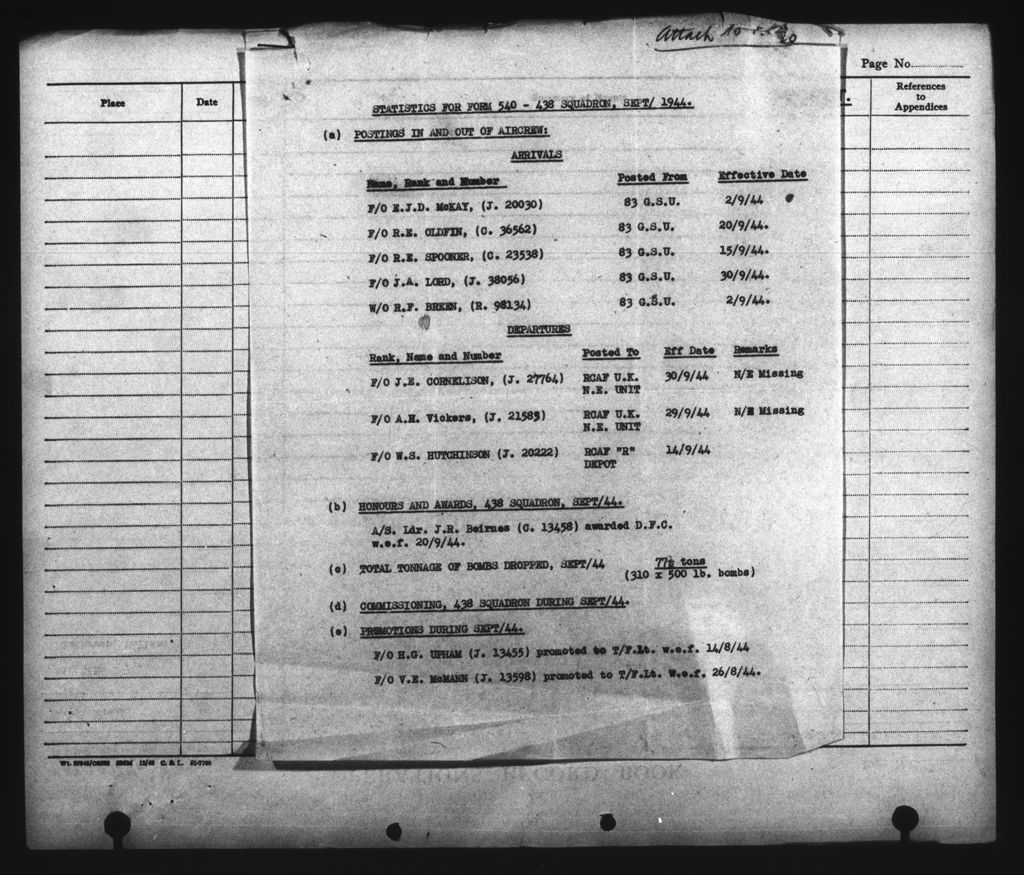

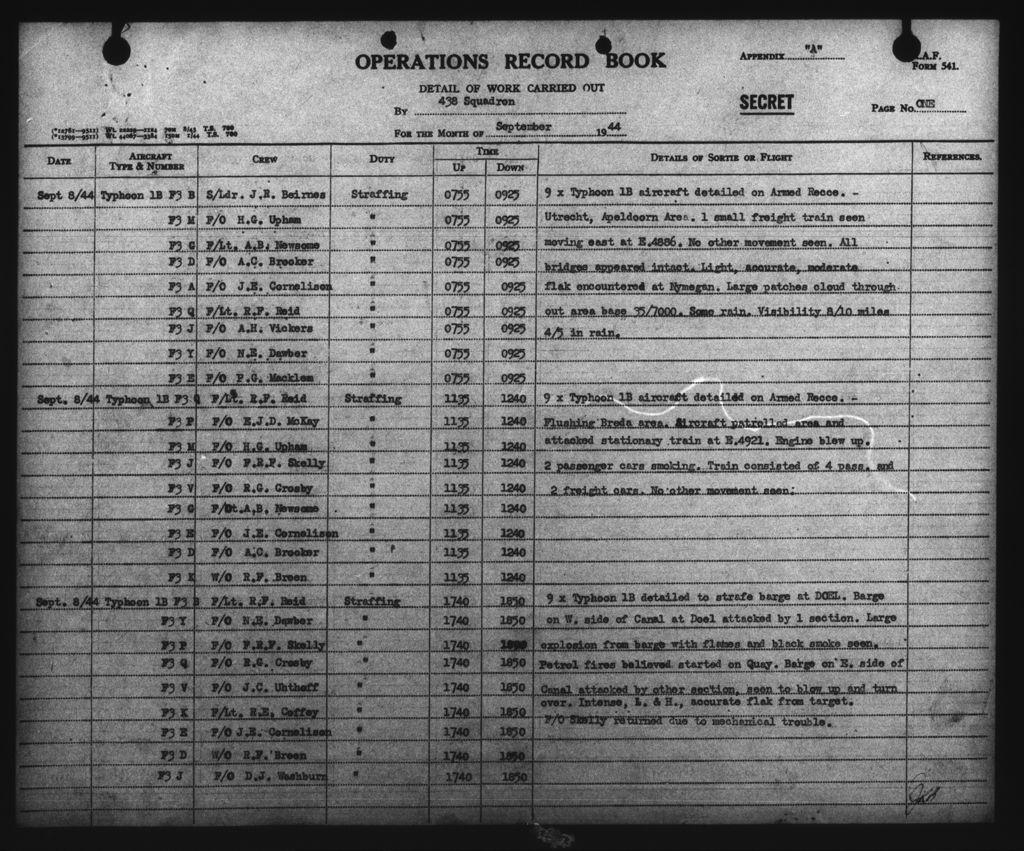

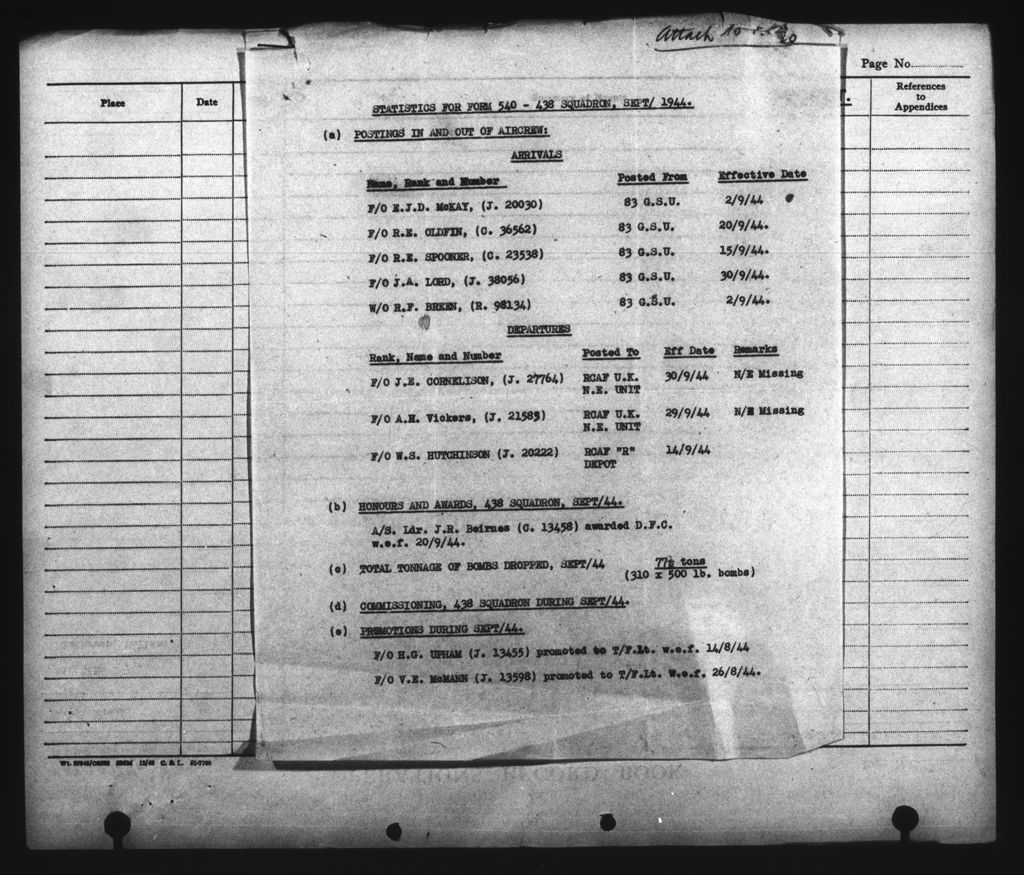

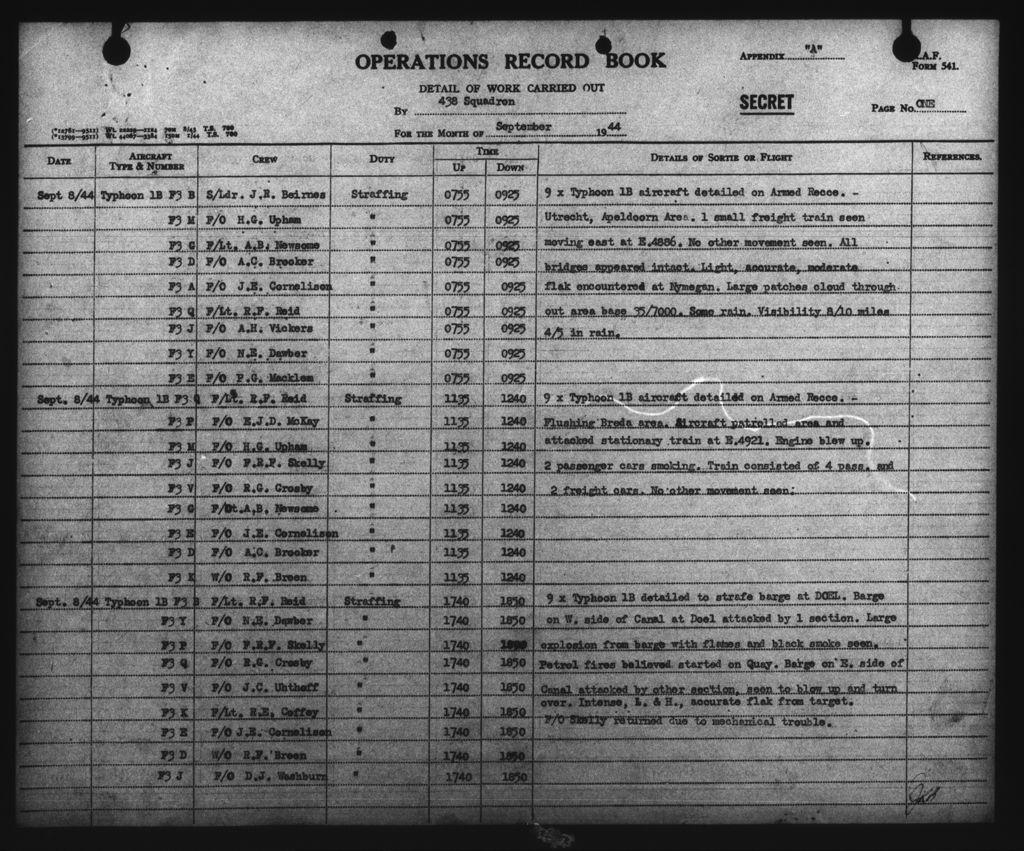

At some point, post-war, he wrote "That Magnificent Flying Machine - The Typhoon". Harry Hardy, 440 Squadron had a copy. Both men were members of the Canadian Fighter Pilots Association. In this six and a half page tribute to the Typhoon, he explains to the reader the nuts and bolts of the aircraft, calling it 'The Monster' at one point. He wrote, "When conversation turns to the subject of WWII and I am asked sometimes what part I played in those long-ago events, my reply that I was a fighter pilot in the RCAF often evokes two questions. What did I fly and how many planes did I shoot down? When I answer that I flew Hurricanes, Spitfires and Typhoons, and that I did not shoot anyone down, there is usually a puzzled pause, especially among non-Air Force types." He provides some statistics, sources unknown. "One report has it that 135 of the first 142 Typhoons delivered were involved in accidents of some kind or other." He tells of the Typhoon's ability to absorb flak damage and remain flyable, saving many pilots' lives and them from becoming POWs. "From March 20, 1944 to May 4, 1945, 438 Squadron flew 4022 sorties. In this time, they dropped 2070 tons of bombs. Although they accounted for only two enemy aircraft, they destroyed five vital bridges, and damaged/destroyed 184/169 vehicles, 12/3 tanks, 4/73 locomotives and 101/532 trains. As well, they inflicted considerable damage on marshalling yards, German strongpoints, and other key targets. In this 13 1/2 month period, 28 aircraft were lost and 31 pilots of whom 17 were killed, five missing, six POW, three later reported safe and three ground personnel were killed."

Edmund was married to Blanche McKay for 58 years. They had six children and four grandchildren. In his obituary, he was "man of deep faith and belief in the Lord. A man of great integrity, character, strength, compassion, devotion and love. RAF/RCAF Fighter Pilot, very proud Canadian, humanitarian, sweetheart, lover of symphonies, excellent food and helping those in need."